William Tyndale’s name is written in the blood of English history, not merely as a scholar or translator, but as a martyr who gave his life so that ordinary men and women could read the Word of God in their own tongue. His death in 1536 was not simply the tragic end of a life devoted to Scripture; it was the turning point in the English Reformation and a defining moment in the story of freedom of faith and expression.

The Crime of Translation

In the early 16th century, England was a land where the Bible was chained literally and spiritually. The Scriptures, confined to Latin, belonged to the clergy and the learned. Ordinary believers depended on priests to interpret God’s Word for them. To translate the Bible into English without church authorization was considered heresy, punishable by death.

Into this world stepped William Tyndale, a brilliant linguist educated at Oxford and Cambridge. Inspired by the growing reformist spirit sweeping Europe, and deeply moved by the teachings of Erasmus and Martin Luther, Tyndale resolved to make the Bible accessible to all Englishmen. “If God spare my life,” he once told a cleric who opposed him, “ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost.”

His conviction made him an outlaw.

Exile and Betrayal

Unable to find approval for his translation in England, Tyndale fled to the continent in 1524. From the safety of Germany and later Antwerp, he labored in secrecy, translating the New Testament from the original Greek; a feat never before accomplished in English. In 1526, the first printed English New Testaments began to circulate in England, smuggled in bales of cloth and barrels of wine.

The authorities were furious. Copies were burned by order of Bishop Tunstall and Sir Thomas More, and agents were sent across Europe to hunt Tyndale down. But he continued his work undeterred, producing revised editions and beginning translations of the Old Testament directly from Hebrew.

His years in exile were years of constant danger, sustained by faith and the quiet support of sympathizers. Yet in 1535, treachery struck. A man named Henry Phillips, posing as a friend, betrayed Tyndale to the authorities in Antwerp. He was arrested and imprisoned in the castle of Vilvoorde, near Brussels.

The Martyrdom at Vilvoorde

For over a year, Tyndale languished in a cold, dark cell. Despite the harsh conditions, he continued to write letters and plead for mercy, not for himself, but for the cause of Scripture. One surviving letter from prison, written in Latin, asks for a warmer coat, a candle, and his Hebrew Bible, so he might continue his translation.

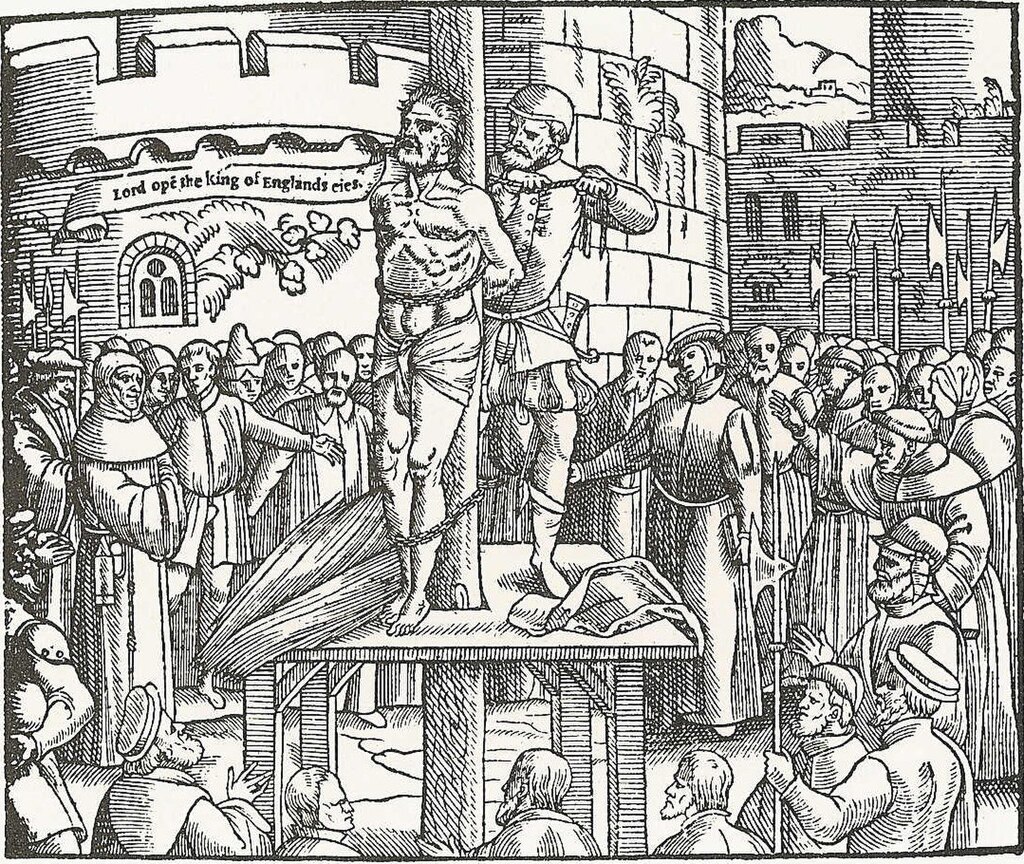

Tyndale was tried for heresy and condemned. On October 6, 1536, he was led out to the stake in the prison yard. There, bound to the post, he prayed his final words, a cry that would echo through history, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes!”

He was strangled first, and then his body burned. The man who had given England its Bible died as a heretic in the eyes of the Church, but as a martyr in the eyes of God and history.

Legacy of the Flame

Tyndale’s prayer was answered within a few short years. In 1539, King Henry VIII authorized the publication of the “Great Bible,” largely based on Tyndale’s work. Though he had been executed as a criminal, his words became the foundation of every major English Bible to follow, from the Geneva Bible beloved by the Puritans to the King James Version of 1611, where over 80% of the text of the New Testament bears his linguistic imprint.

The rhythms and cadences of Tyndale’s English, “Let there be light,” “the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak,” “the powers that be”, still shape the English language today. But more than that, his work broke the monopoly of the priesthood over Scripture and placed the Bible in the hands of the common people.

Tyndale’s death was not in vain. The flames that consumed his body lit a fire that no power on earth could extinguish.

Conclusion

William Tyndale’s martyrdom stands as a solemn reminder that truth and freedom often come at a terrible cost. His life and death testify to the power of conviction, the belief that every person has the right to read and understand the Word of God. In dying, Tyndale gave life to a nation’s faith and language. His voice still speaks through every Bible opened in English: the voice of a man who died that others might read.

“Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.”

And He did.

Leave a comment