The opening chapter of Genesis (Genesis 1:1–2:3) is one of the most profound theological texts in the Bible. It presents a highly ordered, poetic account of creation in six days, followed by a day of divine rest. This narrative is not merely a cosmological description but a theological proclamation of who God is, His relationship to creation, and humanity’s place within the cosmos.

Literary Structure and Theological Purpose

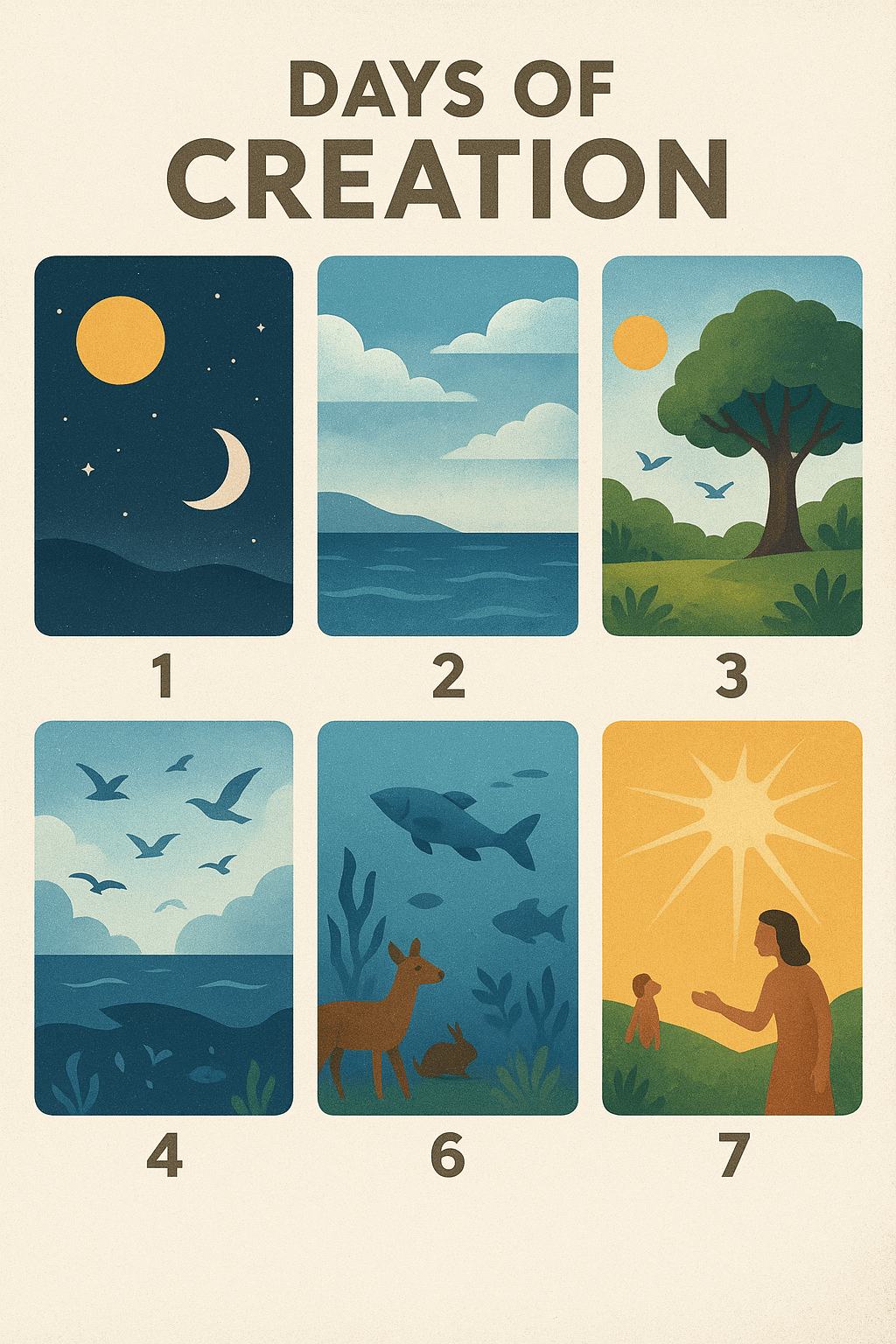

Genesis 1 employs a carefully structured literary pattern. Each day follows a similar formula: a divine command (“And God said…”), the fulfillment of the command (“And it was so”), divine approval (“God saw that it was good”), and the concluding refrain marking the passage of time (“And there was evening and there was morning…”). Many scholars note that the six days form two triads:

Days 1–3: God forms realms (light/darkness, sky/waters, land/vegetation).

Days 4–6: God fills those realms (sun/moon/stars, birds/fish, animals/humans).

This framework hypothesis underscores that God is a God of order, bringing cosmos (order) out of chaos (Hebrew: tohu va-bohu, “formless and void”).

Day 1: Light and Darkness

“In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” (bereshit bara Elohim et hashamayim ve’et ha’aretz). The verb bara (“create”) is used uniquely of divine activity, emphasizing God’s sovereign power. Light (or) is the first created reality, symbolizing God’s presence and inaugurating the cycle of day and night. Some theologians see here a theological polemic against ancient Near Eastern myths that personified light and darkness as deities—Genesis asserts that light itself is a creature, subject to God.

Day 2: The Expanse of the Sky

God creates the raqia (expanse, firmament) to separate the “waters above” from the “waters below.” In the ancient Near Eastern worldview, the sky was perceived as a solid dome. The text affirms that God establishes order in the midst of primordial chaos, setting boundaries for the waters—a theme that recurs throughout Scripture (e.g., Psalm 104:9).

Day 3: Land, Seas, and Vegetation

The emergence of dry land (yabashah) and the naming of “Earth” (eretz) and “Seas” (yamim) reveal God’s sovereignty in assigning identity and function. The creation of vegetation, each “according to its kind,” introduces the theme of fertility and provision. The repeated emphasis on “seed” (zera) foreshadows later biblical themes of covenant and promise (Genesis 12:7; 17:7).

Day 4: Sun, Moon, and Stars

The luminaries are created not as deities but as functionaries—“greater light” and “lesser light” (ma’or gadol, ma’or qaton). The text avoids naming them “sun” and “moon,” possibly to reject their worship in surrounding pagan cultures. Their purpose is functional: to govern time, mark festivals (moedim), and provide light. This ties creation to Israel’s liturgical calendar and the rhythm of sacred time.

Day 5: Birds and Sea Creatures

God populates the waters with nephesh chayyah (“living creatures”) and the skies with birds. The divine blessing to “be fruitful and multiply” is the first blessing in Scripture, indicating that reproduction and abundance are part of God’s good design.

Day 6: Land Animals and Humanity

Land animals are created, again “according to their kinds.” Then comes the climactic moment: the creation of humanity (adam). Unlike other creatures, humans are made “in the image of God” (tselem Elohim), a phrase that has sparked centuries of theological reflection. Scholars debate whether this image refers to rationality, moral capacity, relationality, or a royal function as God’s vice-regents over creation. Humanity is given the cultural mandate to “rule” (radah) and “subdue” (kabash) the earth, emphasizing stewardship rather than exploitation.

Day 7: The Sabbath Rest

God “rested” (shabat) on the seventh day, not because He was weary but because His work was complete. The seventh day is blessed and sanctified, establishing a rhythm of work and rest that becomes central to Israel’s identity (Exodus 20:8–11). Theologically, the Sabbath points beyond creation toward eschatological rest, ultimately fulfilled in Christ (Hebrews 4:9–10).

Theological Implications

1. Monotheism and Polemic: Genesis 1 stands in stark contrast to polytheistic creation myths. There is no cosmic struggle—only the effortless word of God bringing all into being.

2. God’s Sovereignty and Goodness: Repetition of “it was good” (ki tov) affirms that creation is inherently good, a reflection of the Creator’s character.

3. Human Dignity and Responsibility: Being made in God’s image grants humanity unique worth and calls for responsible stewardship over creation.

4. Sabbath Theology: The seventh day models a divine pattern of rest, orienting human life toward worship and trust in God’s provision.

Conclusion

The Days of Creation in Genesis are more than an account of beginnings—they are a liturgical, theological, and philosophical declaration. They invite readers to see the world as God’s ordered sanctuary, humanity as His image-bearers, and time itself as a gift marked by rhythm and holiness. Whether approached literally, figuratively, or as a theological framework, Genesis 1–2 remains foundational for understanding God, creation, and humanity’s vocation within the divine plan.

Leave a comment